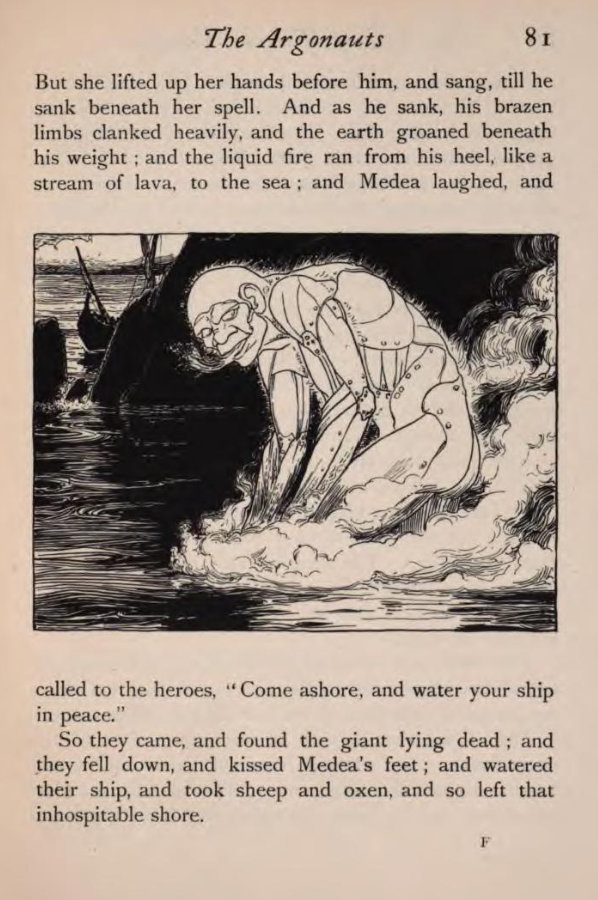

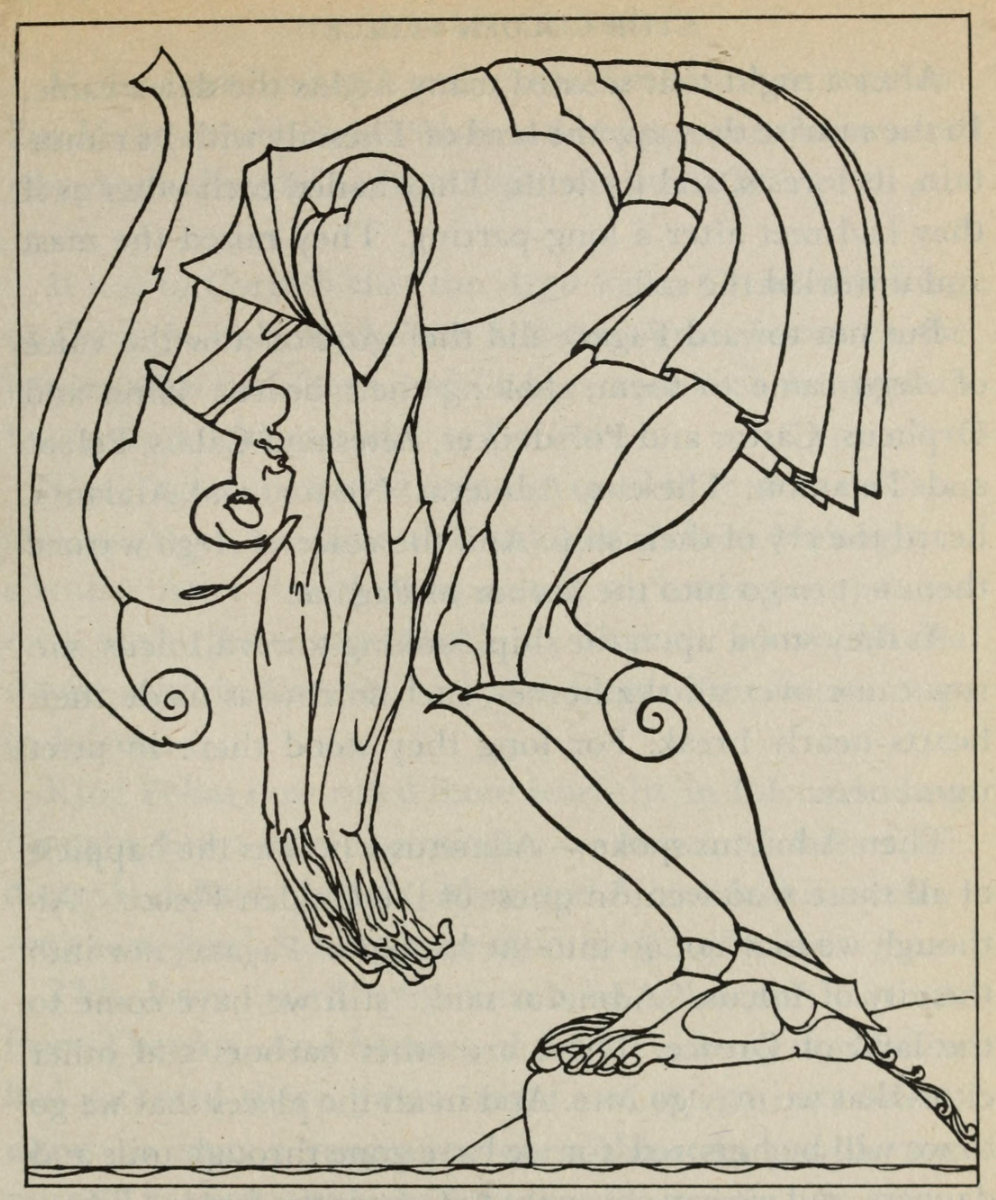

As Adrienne Mayor, a classicist at Stanford University, argues in her 2018 book Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines and Ancient Dreams of Technology, “Long before the clockwork contraptions of the Middle Ages and the [automatons] of early modern Europe… ideas about making artificial life—and qualms about replicating nature—were explored in Greek myths.” One such ancient story centers on the bronze sentry Talos. Forged by Hephaestus, the Greek god of smiths and artisans, Talos was said to have guarded the island of Crete, off the coast of Greece. He patrolled the beaches three times a day, throwing boulders at enemy ships to ward off unwanted visitors to King Minos’ domain. The Argonautica, an epic poem written by Apollonius of Rhodes in the third century B.C.E., chronicles the adventures of Jason and the Argonauts, including their encounter with Talos. After retrieving the legendary golden fleece, the heroes attempt to land on Crete’s shores but find themselves blocked by Talos. Jason’s lover, the sorceress Medea, starts singing, invoking “the death spirits, devourers of life, the swift hounds of Hades,” according to a 20th-century translation of the Argonautica. She then directs “her hostile glance” toward Talos, bewitching him into grazing his ankle, which holds his only vulnerability. “Talos for a while stood on his tireless feet, swaying to and fro, then at last, all strengthless, fell with a mighty thud,” the translation states. In some ways, this interaction might seem like a typical anecdote of an ancient hero and heroine meeting a divinely created obstacle and outsmarting their enemy. Entities magically endowed with life by the gods are not a rarity in Greek myth. Consider, for example, Galatea, a statue of a woman sculpted by Pygmalion as art, then brought to life by Aphrodite. Unlike Galatea, whose “realism became reality supernaturally,” Talos was not merely created “by magic spells or divine fiat,” writes Mayor. He was said to be engineered by Hephaestus, or rather “made, not born,” in a process the ancients “might have called biotechne, from bios ‘life’ and techne, ‘crafted through art or science.'”

| Alias Talos, Talus |

| Real Names/Alt Names N/A |

| Characteristics Myths & Legends, Giant, Robot, Bronze Age, Greek |

| Creators/Key Contributors Unknown |

| First Appearance Greek mythology |

| First Publisher ○ |

| Appearance List Literature: Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica (3rd century BC), The Argonautica by Gaius Valerius Flaccus (late 1st century AD), Bulfinch’s Mythology (1913), et. al. |

| Sample Read Tales of Ancient Greece [Internet Archive] |

| Description As Adrienne Mayor, a classicist at Stanford University, argues in her 2018 book Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines and Ancient Dreams of Technology, “Long before the clockwork contraptions of the Middle Ages and the [automatons] of early modern Europe… ideas about making artificial life—and qualms about replicating nature—were explored in Greek myths.” One such ancient story centers on the bronze sentry Talos. Forged by Hephaestus, the Greek god of smiths and artisans, Talos was said to have guarded the island of Crete, off the coast of Greece. He patrolled the beaches three times a day, throwing boulders at enemy ships to ward off unwanted visitors to King Minos’ domain. The Argonautica, an epic poem written by Apollonius of Rhodes in the third century B.C.E., chronicles the adventures of Jason and the Argonauts, including their encounter with Talos. After retrieving the legendary golden fleece, the heroes attempt to land on Crete’s shores but find themselves blocked by Talos. Jason’s lover, the sorceress Medea, starts singing, invoking “the death spirits, devourers of life, the swift hounds of Hades,” according to a 20th-century translation of the Argonautica. She then directs “her hostile glance” toward Talos, bewitching him into grazing his ankle, which holds his only vulnerability. “Talos for a while stood on his tireless feet, swaying to and fro, then at last, all strengthless, fell with a mighty thud,” the translation states. In some ways, this interaction might seem like a typical anecdote of an ancient hero and heroine meeting a divinely created obstacle and outsmarting their enemy. Entities magically endowed with life by the gods are not a rarity in Greek myth. Consider, for example, Galatea, a statue of a woman sculpted by Pygmalion as art, then brought to life by Aphrodite. Unlike Galatea, whose “realism became reality supernaturally,” Talos was not merely created “by magic spells or divine fiat,” writes Mayor. He was said to be engineered by Hephaestus, or rather “made, not born,” in a process the ancients “might have called biotechne, from bios ‘life’ and techne, ‘crafted through art or science.'” |

| Source Was Talos, the Bronze Automaton Who Guarded the Island of Crete in Greek Myth, an Early Example of Artificial Intelligence? – Smithsonian Magazine |