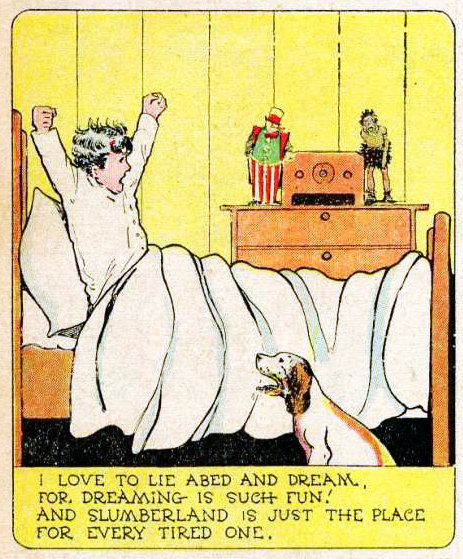

Little Nemo is a fictional character created by American cartoonist Winsor McCay. He originated in an early comic strip by McCay, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, before receiving his own spin-off series, Little Nemo in Slumberland. The strip is considered McCay’s masterpiece for its experiments with the form of the comics page, its use of color and perspective, its timing and pacing, the size and shape of its panels, and its architectural and other details. Little Nemo in Slumberland ran in the New York Herald from October 15, 1905, until July 23, 1911. The strip was renamed In the Land of Wonderful Dreams when McCay brought it to William Randolph Hearst’s New York American, where it ran from September 3, 1911, until July 26, 1914. When McCay returned to the Herald in 1924, he revived the strip, and it ran under its original title from August 3, 1924, until January 9, 1927, when McCay returned to Hearst. Young Nemo (“No one” in Latin) dreamed himself into wondrous predicaments from which he awoke in bed in the last panel. The first episode begins with a command from King Morpheus of Slumberland to a minion to collect Nemo. Nemo was to be the playmate of Slumberland’s Princess, but it took months of adventures before Nemo finally arrived; a green, cigar-chewing clown named Flip was determined to disturb Nemo’s sleep with a top hat emblazoned with the words “Wake Up.” Nemo and Flip eventually become companions, and are joined by an African Imp whom Flip finds in the Candy Islands. The group travels far and wide, from shanty towns to Mars, to Jack Frost’s palace, to the bizarre architecture and distorted funhouse-mirror illusions of Befuddle Hall. The strip shows McCay’s understanding of dream psychology, particularly of dream fears—falling, drowning, impalement. This dream world has its own moral code, perhaps difficult to understand. Breaking it has terrible consequences, as when Nemo ignores instructions not to touch Queen Crystalette, who inhabits a cave of glass. Overcome with his infatuation, he causes her and her followers to shatter, and awakens with “the groans of the dying guardsmen still ringing in his ears”. On July 12, 1908, Flip visits Nemo and tells him that he has had his uncle destroy Slumberland. (Slumberland had been dissolved before, into day, but this time it appeared to be permanent.) After this, Nemo’s dreams take place in his home town, though Flip—and a curious-looking boy named the Professor—accompany him. These adventures range from the down-to-earth to Rarebit-fiend type fantasy; one very commonplace dream had the Professor pelting people with snowballs. The famous “walking bed” story was in this period. Slumberland continued to make sporadic appearances until it returned for good on December 26, 1909. Story-arcs included Befuddle Hall, a voyage to Mars (with a well-realized Martian civilization), and a trip around the world (including a tour of New York City). McCay experimented with the form of the comics page, its timing and pacing, the size and shape of its panels, perspective, and architectural and other detail. From the second installment, McCay had the panel sizes and layouts conform to the action in the strip: as a forest of mushrooms grew, so did the panels, and the panels shrank as the mushrooms collapsed on Nemo. In an early Thanksgiving episode, the focal action of a giant turkey gobbling Nemo’s house receives an enormous circular panel in the center of the page. McCay also accommodated a sense of proportion with panel size and shape, showing elephants and dragons at a scale the reader could feel in proportion to the regular characters. McCay controlled narrative pacing through variation or repetition, as with equally-sized panels whose repeated layouts and minute differences in movement conveyed a feeling of buildup to some climactic action. In his familiar Art Nouveau-influenced style, McCay outlined his characters in heavy blacks. Slumberland’s ornate architecture was reminiscent of the architecture designed by McKim, Mead & White for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, as well as Luna Park and Dreamland in Coney Island, and the Parisian Luxembourg Palace. McCay made imaginative use of color, sometimes changing the backgrounds’ or characters’ colors from panel to panel in a psychedelic imitation of a dream experience. The colors were enhanced by the careful attention and advanced Ben Day lithographic process employed by the Herald’s printing staff. McCay annotated the Nemo pages for the printers with the precise color schemes he wanted.

| Alias Little Nemo in Slumberland |

| Real Names/Alt Names Nemo |

| Characteristics Belle Époque, Juvenile |

| Creators/Key Contributors Winsor McCay |

| First Appearance “Little Nemo in Slumberland” in the New York Herald (1905) |

| First Publisher New York Herald |

| Appearance List Comic Strips: Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905-1911), In the Land of Wonderful Dreams (1911-1914), Little Nemo in Slumberland (1924-1926). Comic books: Star Comics #4-6, Cocomalt Big Book of Comics #1 (Spring 1938), Yankee Comics #1, Punch Comics #9, 11, Kayo Comics #12, Red Seal Comics #14-16, Jest Comics #11. |

| Sample Read Little Nemo [DCM] [CB+] |

| Description Little Nemo is a fictional character created by American cartoonist Winsor McCay. He originated in an early comic strip by McCay, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, before receiving his own spin-off series, Little Nemo in Slumberland. The strip is considered McCay’s masterpiece for its experiments with the form of the comics page, its use of color and perspective, its timing and pacing, the size and shape of its panels, and its architectural and other details. Little Nemo in Slumberland ran in the New York Herald from October 15, 1905, until July 23, 1911. The strip was renamed In the Land of Wonderful Dreams when McCay brought it to William Randolph Hearst’s New York American, where it ran from September 3, 1911, until July 26, 1914. When McCay returned to the Herald in 1924, he revived the strip, and it ran under its original title from August 3, 1924, until January 9, 1927, when McCay returned to Hearst. Young Nemo (“No one” in Latin) dreamed himself into wondrous predicaments from which he awoke in bed in the last panel. The first episode begins with a command from King Morpheus of Slumberland to a minion to collect Nemo. Nemo was to be the playmate of Slumberland’s Princess, but it took months of adventures before Nemo finally arrived; a green, cigar-chewing clown named Flip was determined to disturb Nemo’s sleep with a top hat emblazoned with the words “Wake Up.” Nemo and Flip eventually become companions, and are joined by an African Imp whom Flip finds in the Candy Islands. The group travels far and wide, from shanty towns to Mars, to Jack Frost’s palace, to the bizarre architecture and distorted funhouse-mirror illusions of Befuddle Hall. The strip shows McCay’s understanding of dream psychology, particularly of dream fears—falling, drowning, impalement. This dream world has its own moral code, perhaps difficult to understand. Breaking it has terrible consequences, as when Nemo ignores instructions not to touch Queen Crystalette, who inhabits a cave of glass. Overcome with his infatuation, he causes her and her followers to shatter, and awakens with “the groans of the dying guardsmen still ringing in his ears”. On July 12, 1908, Flip visits Nemo and tells him that he has had his uncle destroy Slumberland. (Slumberland had been dissolved before, into day, but this time it appeared to be permanent.) After this, Nemo’s dreams take place in his home town, though Flip—and a curious-looking boy named the Professor—accompany him. These adventures range from the down-to-earth to Rarebit-fiend type fantasy; one very commonplace dream had the Professor pelting people with snowballs. The famous “walking bed” story was in this period. Slumberland continued to make sporadic appearances until it returned for good on December 26, 1909. Story-arcs included Befuddle Hall, a voyage to Mars (with a well-realized Martian civilization), and a trip around the world (including a tour of New York City). McCay experimented with the form of the comics page, its timing and pacing, the size and shape of its panels, perspective, and architectural and other detail. From the second installment, McCay had the panel sizes and layouts conform to the action in the strip: as a forest of mushrooms grew, so did the panels, and the panels shrank as the mushrooms collapsed on Nemo. In an early Thanksgiving episode, the focal action of a giant turkey gobbling Nemo’s house receives an enormous circular panel in the center of the page. McCay also accommodated a sense of proportion with panel size and shape, showing elephants and dragons at a scale the reader could feel in proportion to the regular characters. McCay controlled narrative pacing through variation or repetition, as with equally-sized panels whose repeated layouts and minute differences in movement conveyed a feeling of buildup to some climactic action. In his familiar Art Nouveau-influenced style, McCay outlined his characters in heavy blacks. Slumberland’s ornate architecture was reminiscent of the architecture designed by McKim, Mead & White for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, as well as Luna Park and Dreamland in Coney Island, and the Parisian Luxembourg Palace. McCay made imaginative use of color, sometimes changing the backgrounds’ or characters’ colors from panel to panel in a psychedelic imitation of a dream experience. The colors were enhanced by the careful attention and advanced Ben Day lithographic process employed by the Herald’s printing staff. McCay annotated the Nemo pages for the printers with the precise color schemes he wanted. |

| Source Little Nemo – Wikipedia |